-40%

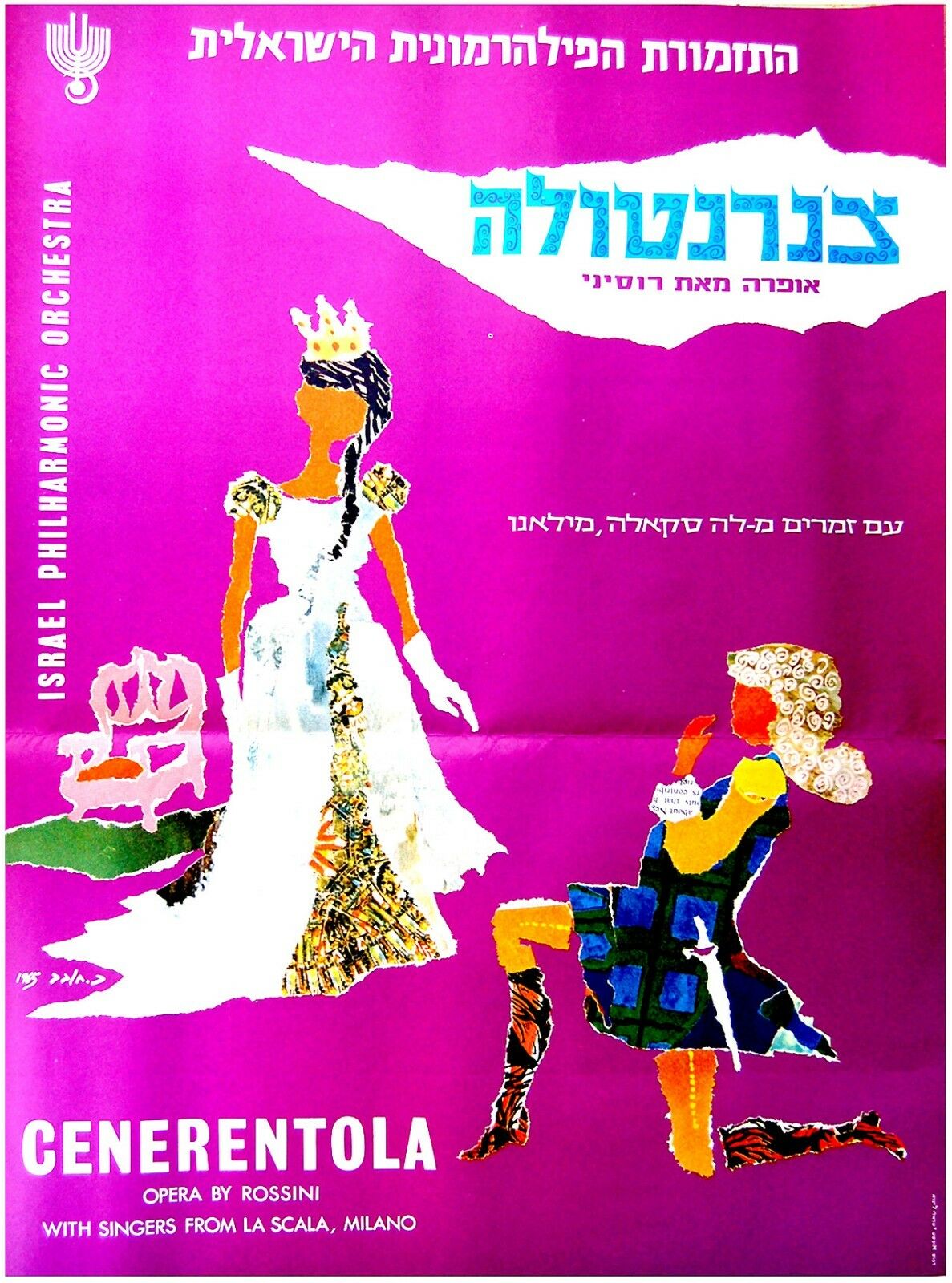

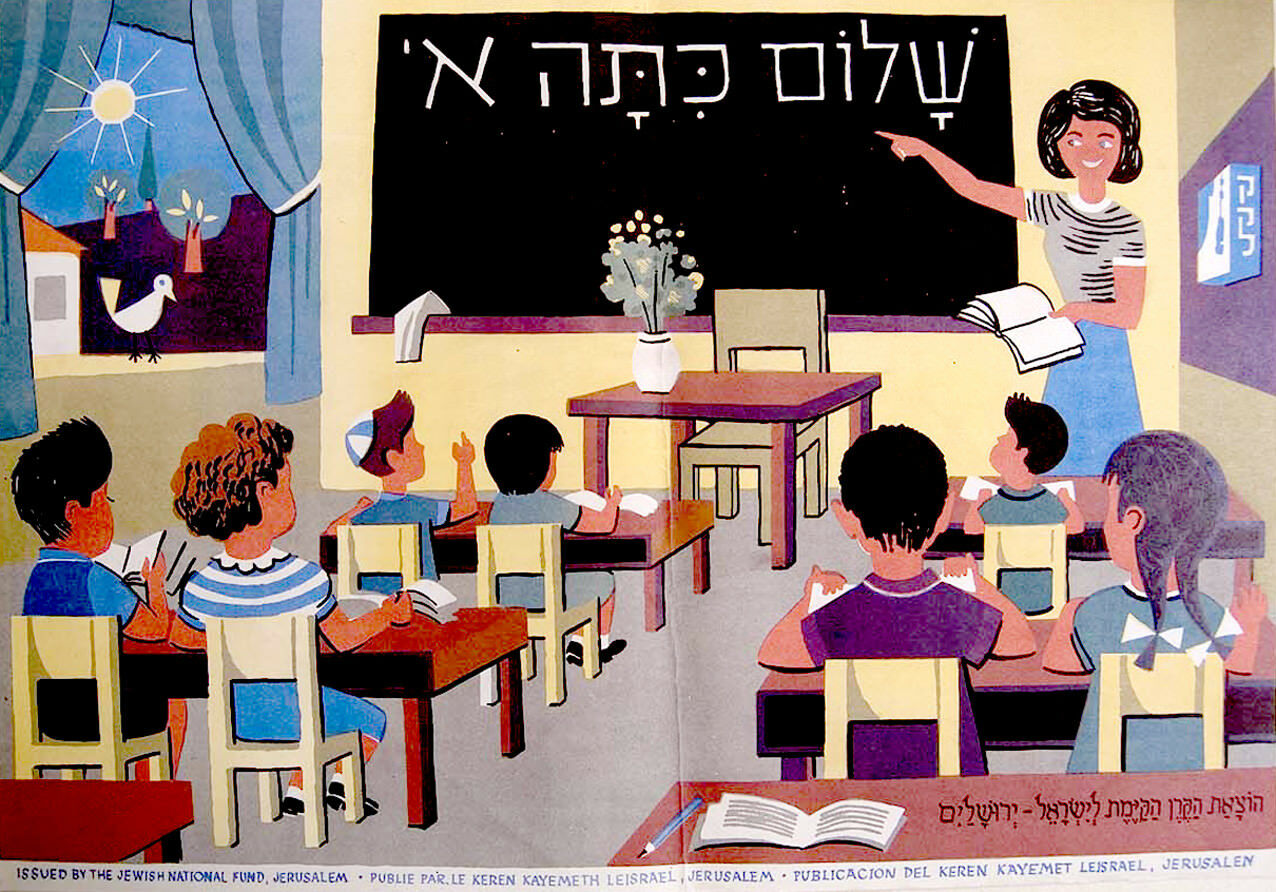

1966 Italian OPERA POSTER Israel CENERENTOLA CINDERELLA Hebrew LA SCALA Jewish

$ 71.28

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

Here for sale is a genuine authentic vintage original almost 50 years old Jewish - Hebrew - Israeli ILLUSTRATED OPERA POSTER , Advertising a production of "CENERENTOLA" ( CINDERELLA

) by GIOACHINO ROSSINI which took place in 1966 Israel. The opera was performed by a group of OPERA SINGERS from LA SCALA in Milan Italy. The LA SCALA Italian group was a visitor of the Israeli IPO

. A colorful illustrated LITHO-OFFSET Printing . A maginicent collage of torn pieces of paper. The poster GIANT SIZE is around 27.5" x 39.5" . Printed on thin stock. Very good condition. Folds.

( Please look at scan for actual AS IS images )

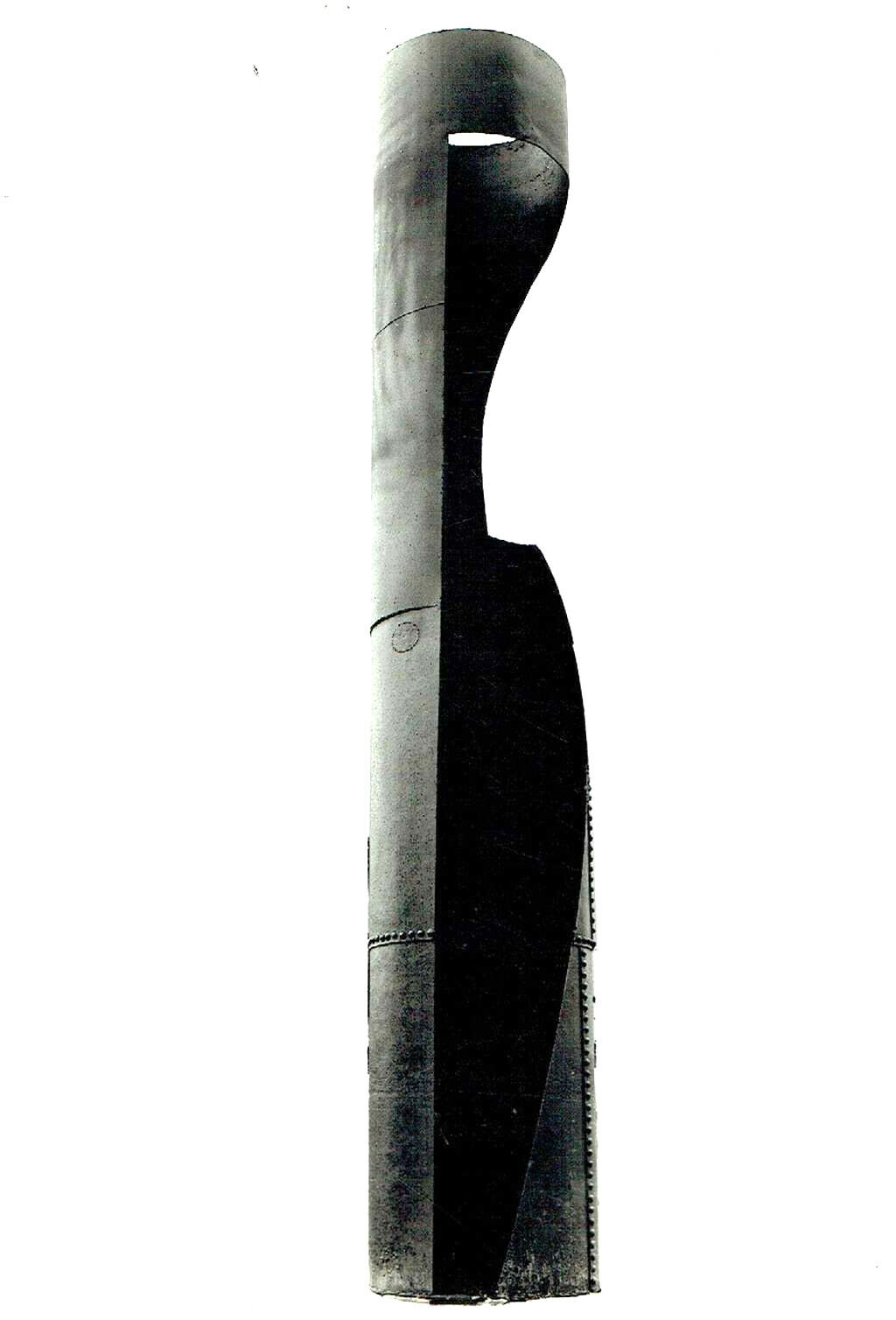

Poster will be sent rolled in a special protective rigid sealed tube.

PAYMENTS

:

Payment method accepted : Paypal .

SHIPPING

:

Shipp worldwide via registered airmail is $ 25 . Poster will be sent rolled in a special protective rigid sealed tube.

Handling around 5 days after payment.

La Cenerentola, ossia La bontà in trionfo (Cinderella, or Goodness Triumphant) is an operatic dramma giocoso in two acts by Gioachino Rossini. The libretto was written by Jacopo Ferretti, based on the fairy tale Cendrillon by Charles Perrault. The opera was first performed in Rome's Teatro Valle on 25 January 1817. Rossini composed La Cenerentola when he was 25 years old, following the success of The Barber of Seville the year before. La Cenerentola, which he completed in a period of three weeks, is considered to have some of his finest writing for solo voice and ensembles. Rossini saved some time by reusing an overture from La gazzetta and part of an aria from The Barber of Seville and by enlisting a collaborator, Luca Agolini, who wrote the secco recitatives and three numbers (Alidoro's "Vasto teatro è il mondo", Clorinda's "Sventurata!" and the chorus "Ah, della bella incognita"). The facsimile edition of the autograph has a different aria for Alidoro, "Fa' silenzio, odo un rumore"; this seems to have been added by an anonymous hand for an 1818 production. For an 1820 revival in Rome, Rossini wrote a bravura replacement, "La, del ciel nell'arcano profondo". The light, energetic overture has been in the standard repertoire since its premiere as La Cenerentola.Performance history19th centuryAt the first performance, the opera was received with some hostility,[1] but it soon became popular throughout Italy and beyond; it reached Lisbon in 1819,[2] London in 1820 and New York in 1826. Throughout most of the 19th century, its popularity rivalled that of Barber, but as the coloratura contralto, for which the role was originally written, became rare it fell slowly out of the repertoire.20th century and beyond However, from the 1960s onward, as Rossini enjoyed a renaissance, a new generation of Rossini mezzo-sopranos and contraltos ensured the renewed popularity of the work. There are changes from the traditional fairy tale in La Cenerentola because Rossini opted for having a non-magical resolution to the story (unlike the original source), due to obvious limitations in the "special effects" available. There are a number of recordings of the opera, and, as a staple of the standard operatic repertoire, it appears as number 28 on the Operabase list of the most-performed operas worldwide.[3] . La Scala (abbreviation in Italian language for the official name Teatro alla Scala) is a world-renowned opera house in Milan, Italy. The theatre was inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and was originally known as the New Royal-Ducal Theatre alla Scala (Nuovo Regio Ducale Teatro alla Scala). The premiere performance was Antonio Salieri's Europa riconosciuta.Most of Italy's greatest operatic artists, and many of the finest singers from around the world, have appeared at La Scala during the past 200 years. Today, the theatre is still recognised as one of the leading opera and ballet theatres in the world and is home to the La Scala Theatre Chorus, La Scala Theatre Ballet and La Scala Theatre Orchestra. The theatre also has an associate school, known as the La Scala Theatre Academy (Italian: Accademia Teatro alla Scala), which offers professional training in music, dance, stage craft and stage management.La Scala's season traditionally opens on 7 December, Saint Ambrose's Day, the feast day of Milan's patron saint. All performances must end before midnight, and long operas start earlier in the evening when necessary.The Museo Teatrale alla Scala (La Scala Theatre Museum), accessible from the theatre's foyer and a part of the house, contains a collection of paintings, drafts, statues, costumes, and other documents regarding La Scala's and opera history in general. La Scala also hosts the Accademia d'Arti e Mestieri dello Spettacolo (Academy for the Performing Arts). Its goal is to train a new generation of young musicians, technical staff, and dancers (at the Scuola di Ballo del Teatro alla Scala, one of the Academy's divisions).A fire destroyed the previous theatre, the Teatro Regio Ducale, on 25 February 1776, after a carnival gala. A group of ninety wealthy Milanese, who owned palchi (private boxes) in the theatre, wrote to Archduke Ferdinand of Austria-Este asking for a new theatre and a provisional one to be used while completing the new one. The neoclassical architect Giuseppe Piermarini produced an initial design but it was rejected by Count Firmian (the governor of the then Austrian Lombardy).A second plan was accepted in 1776 by Empress Maria Theresa. The new theatre was built on the former location of the church of Santa Maria alla Scala, from which the theatre gets its name. The church was deconsecrated and demolished, and over a period of two years the theatre was completed by Pietro Marliani, Pietro Nosetti and Antonio and Giuseppe Fe. The theatre had a total of "3,000 or so" seats[1] organized into 678 pit-stalls, arranged in six tiers of boxes above which is the 'loggione' or two galleries. Its stage is one of the largest in Italy (16.15m d x 20.4m w x 26m h).Building expenses were covered by the sale of palchi, which were lavishly decorated by their owners, impressing observers such as Stendhal. La Scala (as it came to be known) soon became the preeminent meeting place for noble and wealthy Milanese people. In the tradition of the times, the platea (the main floor) had no chairs and spectators watched the shows standing up. The orchestra was in full sight, as the golfo mistico (orchestra pit) had not yet been built.Above the boxes, La Scala has a gallery where the less wealthy can watch the performances, called the loggione. The loggione is typically crowded with the most critical opera aficionados, who can be ecstatic or merciless towards singers' perceived successes or failures. La Scala's loggione is considered a baptism of fire in the opera world, and fiascos are long remembered. (One recent incident occurred in 2006 when tenor Roberto Alagna was booed off the stage during a performance of Aïda, forcing his understudy, Antonello Palombi, quickly to replace him mid-scene without time to change into a costume.)As with most of the theatres at that time, La Scala was also a casino, with gamblers sitting in the foyer.[2] Conditions in the auditorium, too, could be frustrating for the opera lover, as Mary Shelley discovered in September 1840:At the Opera they were giving Otto Nicolai's Templario. Unfortunately, as is well known, the theatre of La Scala serves, not only as the universal drawing-room for all the society of Milan, but every sort of trading transaction, from horse-dealing to stock-jobbing, is carried on in the pit; so that brief and far between are the snatches of melody one can catch.[3]La Scala was originally illuminated with 84 oil lamps mounted on the palcoscenico and another thousand in the rest of theatre. To prevent the risks of fire, several rooms were filled with hundreds of water buckets. In time, oil lamps were replaced by gas lamps, these in turn were replaced by electric lights in 1883.The original structure was renovated in 1907, when it was given its current layout with 2,800 seats. In 1943, during WWII, La Scala was severely damaged by bombing. It was rebuilt and reopened on 11 May 1946, with a memorable concert conducted by Arturo Toscanini—twice La Scala's principal conductor and an associate of the composers Giuseppe Verdi and Giacomo Puccini—with a soprano solo by Renata Tebaldi, which created a sensation.La Scala hosted the prima (first production) of many famous operas, and had a special relationship with Verdi. For several years, however, Verdi did not allow his work to be played here, as some of his music had been modified (he said "corrupted") by the orchestra. This dispute originated in a disagreement over the production of his Giovanna d'Arco in 1845; however the composer later conducted his Requiem there on 25 May 1874 and he announced in 1886 that La Scala would host the premiere of what was to become his penultimate opera, Otello.[4] The premiere of his last opera, Falstaff was also given in the theatre.In 1982, the Filarmonica della Scala was established, drawing its members from the larger pool of musicians that comprise the Orchestra della Scala.Principal conductors/Music directors of La Scala Franco Faccio, (1871–1889)[10] Arturo Toscanini, (1898–1908) Tullio Serafin, (1909–1914, 1917–1918) La Scala closed from 1918 to 1920 Arturo Toscanini, (1921–1929) Victor de Sabata, (1930–1953) Carlo Maria Giulini, (1953–1956) Guido Cantelli, (1956)[11] Gianandrea Gavazzeni, (1966–1968) Claudio Abbado, (1968–1986) Riccardo Muti, (1986–2005) Daniel Barenboim, (2006–2011, Maestro Scaligero; music director effective December 2011) eba2569