-40%

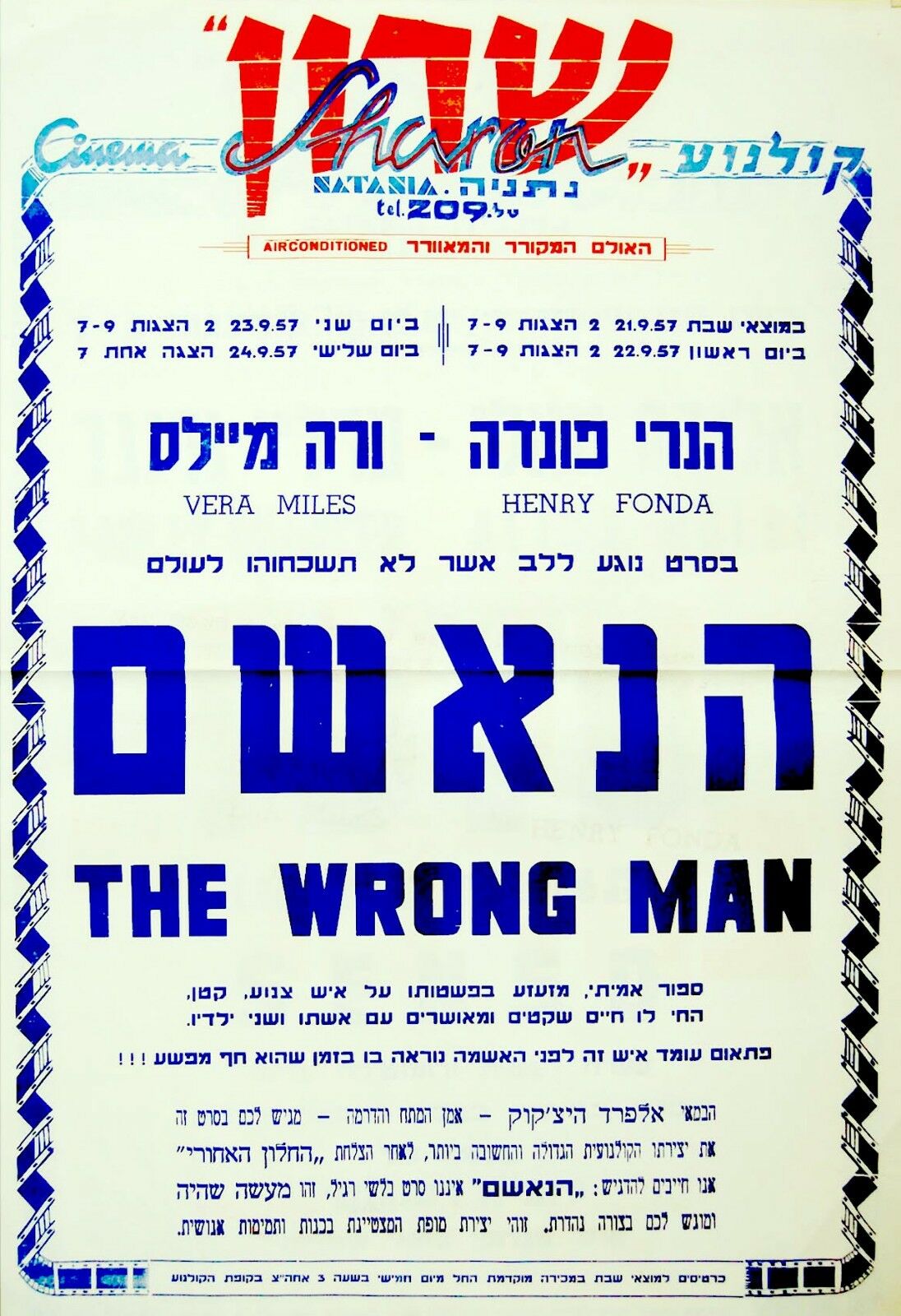

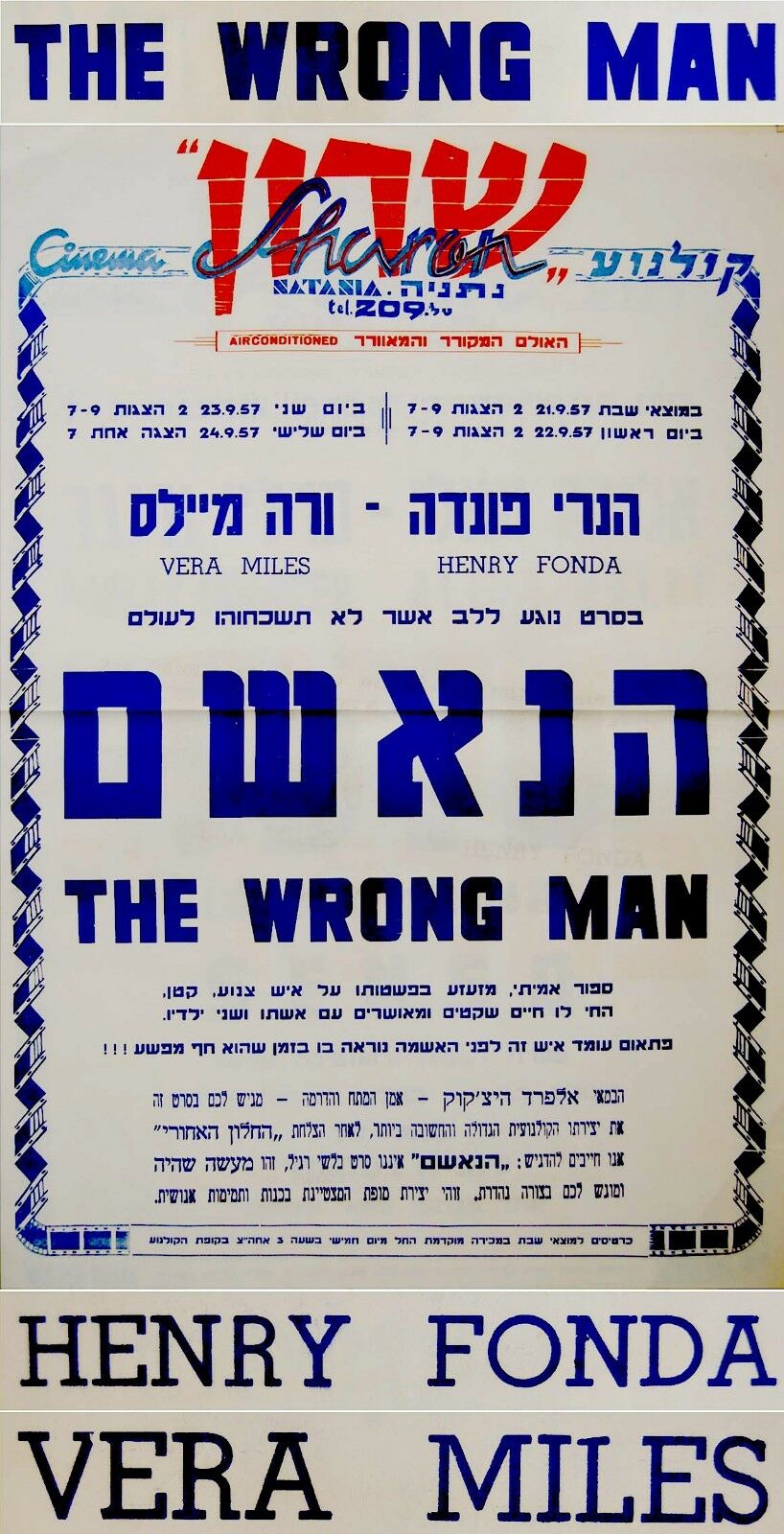

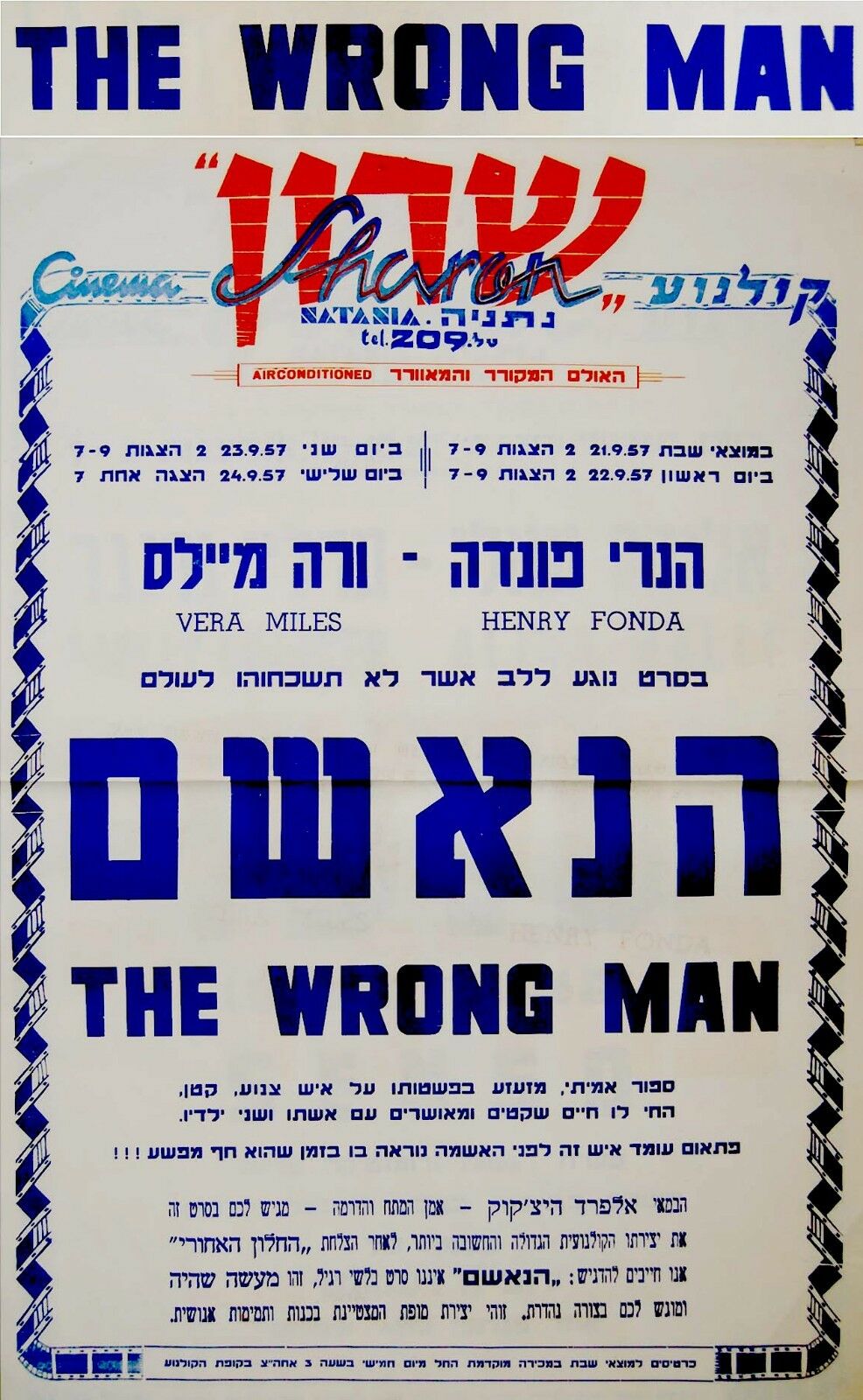

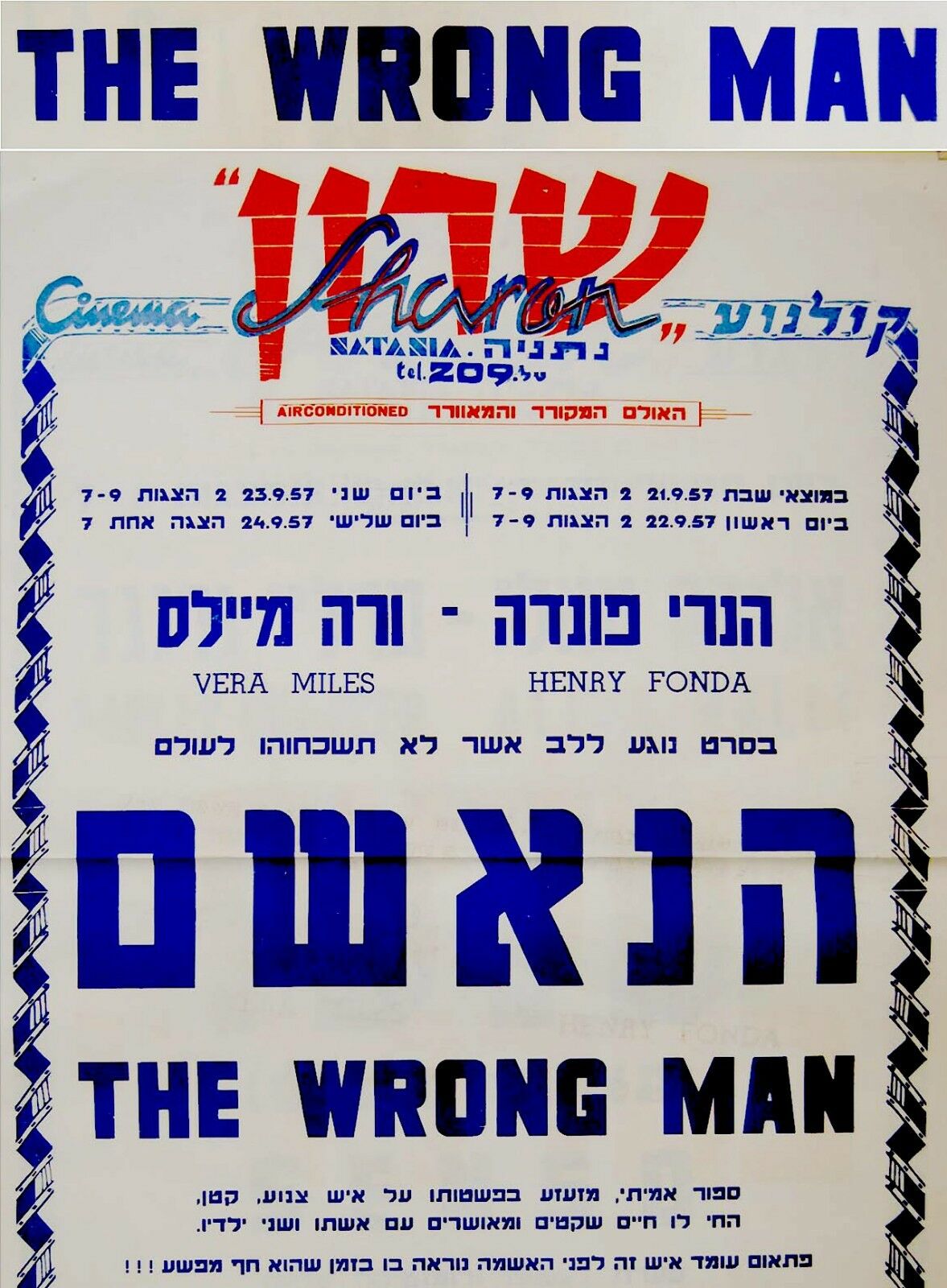

1957 Israel HITCHCOCK Movie POSTER Film THE WRONG MAN Hebrew FONDA Jewish RARE

$ 46.99

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

Here for sale is an almost 65 years old EXCEPTIONALY RARE and ORIGINAL POSTER for the ISRAEL 1957 PREMIERE of ALFRED HITCHCOCK legendary film "THE WRONG MAN" , Starrig among others : HENRY FONDA and VERA MILES in the small rural town of NATHANYA in ISRAEL. The cinema-movie hall " HASHARON" was printing manualy its own posters , And thus you can be certain that this surviving copy is ONE OF ITS KIND. Fully DATED September 1957 . Text in HEBREW and ENGLISH . Please note : This is NOT a re-release poster but PREMIERE - FIRST RELEASE projection of the film , One year after its release in 1956 in USA and worldwide . The ISRAELI distributors of the film have given it an INTERESTING and even quite amusing advertising and promoting accompany text. They gave the film a brand new Israeli name : "The ACCUSED" . Judaica Jewish . GIANT size around 28" x 38" ( Not accurate ) . Printed in red and blue on white paper .

The condition is good . Folded once.

( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images ) Poster will be sent rolled in a special protective rigid sealed tube.

AUTHENTICITY

:

This poster is guaranteed ORIGINAL from 1957 ( Fully dated ) , NOT a reprint or a recently made immitation. , It holds a life long GUARANTEE for its AUTHENTICITY and ORIGINALITY.

PAYMENTS

:

Payment method accepted : Paypal .

SHIPPMENT

:

SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is $ 25. Poster will be sent rolled in a special protective rigid sealed tube. Handling around 5 days after payment.

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock, KBE (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English film director and producer. He pioneered many techniques in the suspense and psychological thriller genres. After a successful career in British cinema in both silent films and early talkies, billed as England's best director, Hitchcock moved to Hollywood in 1939 and became a U.S. citizen in 1955. Over a career spanning more than half a century, Hitchcock fashioned for himself a distinctive and recognisable directorial style. He pioneered the use of a camera made to move in a way that mimics a person's gaze, forcing viewers to engage in a form of voyeurism. He framed shots to maximise anxiety, fear, or empathy, and used innovative film editing. His stories often feature fugitives on the run from the law alongside "icy blonde" female characters. Many of Hitchcock's films have twist endings and thrilling plots featuring depictions of violence, murder, and crime. Many of the mysteries, however, are used as decoys or "MacGuffins" that serve the film's themes and the psychological examinations of the characters. Hitchcock's films also borrow many themes from psychoanalysis and feature strong sexual overtones. Through his cameo appearances in his own films, interviews, film trailers, and the television program

Alfred Hitchcock Presents

he became a cultural icon. Hitchcock directed more than fifty feature films in a career spanning six decades. Often regarded as the greatest British filmmaker, he came first in a 2007 poll of film critics in Britain's

Daily Telegraph

, which said: "Unquestionably the greatest filmmaker to emerge from these islands, Hitchcock did more than any director to shape modern cinema, which would be utterly different without him. His flair was for narrative, cruelly withholding crucial information (from his characters and from us) and engaging the emotions of the audience like no one else." The magazine

MovieMaker

has described him as the most influential filmmaker of all time, and he is widely regarded as one of cinema's most significant artists.

The Wrong Man

is a 1956 film noir by Alfred Hitchcock which stars Henry Fonda and Vera Miles. The film was drawn from the true story of an innocent man charged with a crime, as described in the book,

The True Story of Christopher Emmanuel Balestrero

by Maxwell Anderson, and in the magazine article, "A Case of Identity" (

Life

magazine, June 29, 1953) by Herbert Brean. It was one of the few Hitchcock films based on a true story and whose plot closely followed the real-life events.

The Wrong Man

had a notable effect on two significant directors: it prompted Jean-Luc Godard's longest piece of written criticism, and affected Martin Scorsese's

Taxi Driver

The Wrong Man is a 1956 American docudrama film directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Henry Fonda and Vera Miles.[1][2] The film was drawn from the true story of an innocent man charged with a crime, as described in the book The True Story of Christopher Emmanuel Balestrero by Maxwell Anderson[3][4] and in the magazine article "A Case of Identity" (Life magazine, June 29, 1953) by Herbert Brean.[5] It is one of the few Hitchcock films based on a true story and whose plot closely follows the real-life events. The Wrong Man had a notable effect on two significant directors: it prompted Jean-Luc Godard's longest piece of written criticism in his years as a critic,[6] and it has been cited as an influence on Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver.[7] Contents [hide] 1 Plot 2 Cast 3 Historical notes 4 Production 5 Reception 6 See also 7 References 8 External links Plot[edit] For the only time in his many films, Alfred Hitchcock starts this picture talking to the camera and says that "every word is true" in this story. Manny Balestrero (Henry Fonda), a down-on-his-luck musician at New York City's Stork Club, is in a money crunch. His wife, Rose (Vera Miles), needs to have her wisdom teeth extracted at a cost of 0, but the couple does not have that much money. Though he has already borrowed against his life insurance policy, he goes to the life insurance company to attempt to take a loan out against Rose's policy. He is immediately mistaken by the clerical workers in the store as the man who had twice held up the insurance office. They inform the police, and he is taken to the 110th Precinct by detectives. Without being told why, Manny is instructed to walk in and out of a liquor store and delicatessen, both scenes of a robbery earlier that year. He is then asked by police to give a handwriting sample, writing the words from the stick-up note at the insurance company. Manny misspells the word "drawer" as "draw"—the same spelling mistake the robber made in the note. After being picked out of a police lineup by the women from the insurance company, he is then arrested and charged with robbery, and his family finds out that he will be in court on the following morning. Attorney Frank O'Connor (Anthony Quayle) sets out to prove that Manny cannot possibly be the right man: at the time of the first hold-up he was on vacation with his family, and at the time of the second his jaw was so swollen that witnesses would certainly have noticed. Manny and Rose look for three people who saw Manny at the vacation hotel, but two have died and the third cannot be found. All this devastates Rose, whose resulting depression forces her to be hospitalized. During Manny's trial a juror, bored with the minutiae of one witness' testimony, makes a remark which prompts the judge to declare a mistrial. While Manny is awaiting a second trial, he is exonerated after the true robber is arrested holding up a grocery store. Manny visits Rose at the hospital to share the good news, but, as the film ends, she remains clinically depressed; a textual epilogue explains that she recovered two years later. Cast[edit] Henry Fonda as Christopher Emmanuel "Manny" Balestrero Vera Miles as Rose Balestrero Anthony Quayle as Frank O'Connor Harold J. Stone as Jack Lee Charles Cooper as Det. Matthews John Hildebrand as Tomasini Esther Minciotti as Mama Balestrero Doreen Lang as Ann James Laurinda Barrett as Constance Willis Norma Connolly as Betty Todd Nehemiah Persoff as Gene Conforti Lola D'Annunzio as Olga Conforti Werner Klemperer as Dr. Bannay Kippy Campbell as Robert Balestrero Robert Essen as Gregory Balestrero Richard Robbins as Daniel, the guilty man Cast notes Actors appearing in the film, but not listed in the credits, include Harry Dean Stanton, Werner Klemperer, Tuesday Weld, Patricia Morrow, Bonnie Franklin, and Barney Martin.[8] Weld and Franklin made their film debuts as two giggly girls answering the door when the Balestreros are seeking witnesses to prove his innocence. Historical notes[edit] The real O'Connor (1909–1992) was a former New York State Senator at the time of the trial, and later became the district attorney of Queens County (New York City, New York), the president of the New York City Council and an appellate-court judge. Rose Balestrero (1910–1982) died in Florida at the age of 72.[9] Production[edit] A Hitchcock cameo is typical of most of his films. In The Wrong Man, he appears only in silhouette in a darkened studio, just before the credits at the beginning of the film, announcing that the story is true. Originally, he intended to be seen as a customer walking into the Stork Club, but he edited himself out of the final print.[10] Many scenes were filmed in Jackson Heights, the neighborhood where Manny lived when he was accused. Most of the prison scenes were filmed among the convicts in a New York City prison in Queens. The courthouse was located at the corner of Catalpa Avenue and 64th Street in Ridgewood.[11] Bernard Herrmann composed the soundtrack, as he had for all of Hitchcock's films from The Trouble with Harry (1955) through Marnie (1964). It is one of the most subdued scores Herrmann ever wrote, and one of the few he composed with some jazz elements, here primarily to represent Fonda's appearance as a musician in the nightclub scenes. This was Hitchcock's final film for Warner Bros. It completed a contract commitment that had begun with two films produced for Transatlantic Pictures and released by Warner Brothers: Rope (1948) and Under Capricorn (1949), his first two films in Technicolor. After The Wrong Man, Hitchcock returned to Paramount Pictures. Reception[edit] The Rotten Tomatoes approval rating was 91% in March 2017. “THE WRONG MAN": HITCHCOCK’S LEAST “FUN” MOVIE IS ALSO ONE OF HIS GREATEST by Glenn Kenny February 17, 2016 | 2 Print Page With the possible exception of the 1953 film “I Confess,” Alfred Hitchcock’s 1956 title “The Wrong Man” is the least fun, or “fun,” movie of the master of suspense’s long and incredibly fruitful Hollywood period. Yes, earlier pictures like “Rope” and later pictures such as “Psycho” and “The Birds” went into realms of nearly irremediable darkness but even those pictures had their moments of humor, their inside jokes. For “The Wrong Man,” Hitchcock took his task so sufficiently seriously that he denied himself his usual winking cameo, the appearance (usually early on) of Hitch in some dryly humorous posture interacting with the world he’s creating. The director does appear in the movie, addressing the audience directly in a prologue, but his mien is different than it would be in his droll introductions to the episodes of TV’s “Alfred Hitchcock Presents;” presented in silhouette and long shot, he all but warns his audience that this is a “different” kind of story for him. The difference, we are meant to infer, is in the documentary value: the scenario is based on a true event, and Hitchcock tells it with great attention to realism and verisimilitude (there is a distinction between the two, one that Hitchcock appreciated). But anyone expecting, as a result, a movie devoid of expressive cinematic style, will be pleasantly surprised: this is as fluently styled a movie as Hitchcock ever made. The movie tells the story of Christopher Balestrero, nicknamed “Manny,” a member of the house band at New York’s swanky Stork Club in the early ‘50s, who found himself on the receiving end of a very bad case of mistaken identity, enduring arrest and trial for a series of small-time robberies that he did not commit. Screen icon of integrity Henry Fonda plays Manny and Vera Miles is his wife Rose, who suffers a breakdown and serious attendant depression as a result of the ordeal. Despite his show-biz job, Manny’s a working class guy, stressed about money, making fantasy bets on horses on his subway ride home, flummoxed by his wife’s worry over having to come up with the money for some emergency dental work. Manny comes up with the bright idea of borrowing off an insurance policy, and in that office—located in both real life and the film in a Queens building called the Victor MooreArcade, and yes, it was named after the famed comic actor—he is “recognized” by several tellers as a man who held them up that prior December. And so the nightmare begins. Hitchcock’s crucial style is evident right from the opening credits. Over the credits, there’s a shot of the hopping Stork Club; the largely unseen band plays a lively tune as the camera pans left, and settles on one static view. Then, in a series of very unobtrusive dissolves, the nightclub crowd thins out. The jazzy music, composed by Bernard Herrmann, grows softer, less energetic; by the time we get to the director’s credit, it’s nearly closing time. As Manny walks out of the Stork Club and to the subway, he passes two beat cops, and as the camera follows, a composition resolves itself of the two cops flanking Manny, like, perhaps, protective angels watching over him as he descends to meet his train. From that moment on, though, the police are presented as surly, near-malevolent representatives of a system that wants to place Manny in captivity. (The lead detective in Manny’s case is played by a gruff Harold J. Stone, but the movie’s secret weapon, performer-wise, is Charles Cooper, investing the junior detective with a constant oily smirk that makes him read as an out-and-out villain.) Writing about the film in June of 1957, future director Jean-Luc Godard—in a piece that stands as one of his very best, and most prescient, works of criticism—noted that “Hitchcock has never used an unnecessary shot. Even the most anodyne of them invariably serve the plot, which they enrich rather as the 'touch' beloved of the Impressionists enriched their paintings.” Similarly, in their 1957 book on Hitchcock in which they all but proclaimed “The Wrong Man” the director’s supreme masterpiece, future directors Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol upped that ante by proclaiming, “In Hitchcock’s work form does not embellish content, it creates it.” This is evident throughout “The Wrong Man” in a series of what Godard called “doubled scenes.” The two most obvious ones are the heart-to-heart talks between Manny and Rose in their bedroom. In the first, Hitchcock works around Production Code and Joe Breen censorship restrictions by having Manny sit on Rose’s bed; he leans in to her and holds her as they speak; the two are seen united in the frame, each in profile, as if on the verge of a kiss even as they discuss trying matters like how they’re going to pay to have Rose’s impacted tooth fixed. In the second scene, after Manny’s arrest and release on bail, and as Rose is beginning to crack, they are depicted sitting a good deal apart from each other, and the shot-reverse-shot pattern of their exchange, along with the long shadows, creates the palpable impression of parties opposed to each other. Given how warmly the couple had been heretofore depicted, it’s heartbreaking. The depictions of Manny’s jailing are equally vivid. With the possible exception of a by-now anachronistic tilt-a-whirl camera effect to suggest Manny’s dizziness in his jail cell, this material is handled as impeccably and dynamically as Bresson did in his film “A Man Escaped,” also from 1956. Does a jail cell look different to an innocent man than it does to a guilty man? It’s an interesting question; in both these films the protagonists are free of sin, so to speak, but they are also seeing the inside of a cell for the first time. Godard says that when Manny enters the cell for the first time, he is “seeing without looking,” and that the protagonist of the Bresson film “does the exact opposite”—because, and this difference is crucial, Bresson’s hero has the intention of getting out of there. Manny can see no way out, and the condition of confinement, from the dingy walls of the cells to the dead-click sound of the handcuffs, is rendered with a terrifying attention to detail. Remember that Hitchcock had a lifelong fear of the police, stemming from when his disciplinarian father once took him down to a precinct house on an occasion that the then-boy had misbehaved. Black-and-white has maybe never looked more black and white than in the scene in which Manny sits handcuffed in a traveling police van. Which brings me to the reason I’m now offering these notes of appreciation: a new Blu-ray disc of the movie, just released by the Warner Archive. It is a truly splendid high-def rendition of the film in a 1.77 aspect ratio very close to its theatrical presentation, taken from superior materials. There’s a show of noticeable grain in certain scenes but for the most part the texture is extremely solid; the visuals are striking, compelling. (The screen caps illustrating the Manny and Rose scenes are taken from the standard-def edition; directly above is a screen cap from the DVD Beaver review of the disc, for contrast.) In every other respect it matches the 2004 edition, but the Blu-ray boost is appreciable, and makes this movie, one of Hitchcock’s most dread-filled but also one of his most compassionate (not to mention Catholic), an exemplary home-theater-library item.

.

ebay1590